Mads Kjeldgaard

Space In Between

A problem occurred with the audio player. Here is some debug info:

Title: Mads Kjeldgaard – 15:15 PM (Excerpt)

MP3: /sound/04 - Mads Kjeldgaard - 15_15 PM (Excerpt) (EX001).mp3

ID: 1760199459675737000

CSS ID: jquery_jplayer_1760199459675737000

Container ID: jp_container_1760199459675737000

I approach it like a child: pressing the keys as if for the first time, absorbing the esoteric output that seeps through the wooden enclosure of my pianette. Via the medium of vibrations, it ping pongs in the room and envelops my body. Then silence, or, what we call silence: the trivial sounds of the city. A child crying in a nearby playground, a moped speeding past my apartment building, two old friends wandering down the road as they talk to each other in that unmistakable tonality of complaint.

I started playing Satie’s Gymnopédies on the piano. This happened in a period of intense creative drought. I had nothing else to do, musically, because none of my usual creative outlets interested me. Apropos Satie, he coined the term furniture music: “a music which is like furniture - a music, that is, which will be part of the noises of the environment, will take them into consideration. I think of it as melodious, softening the noises of the knives and forks at dinner, not dominating them, not imposing itself. It would fill up those heavy silences that sometime fall between friends dining together.”

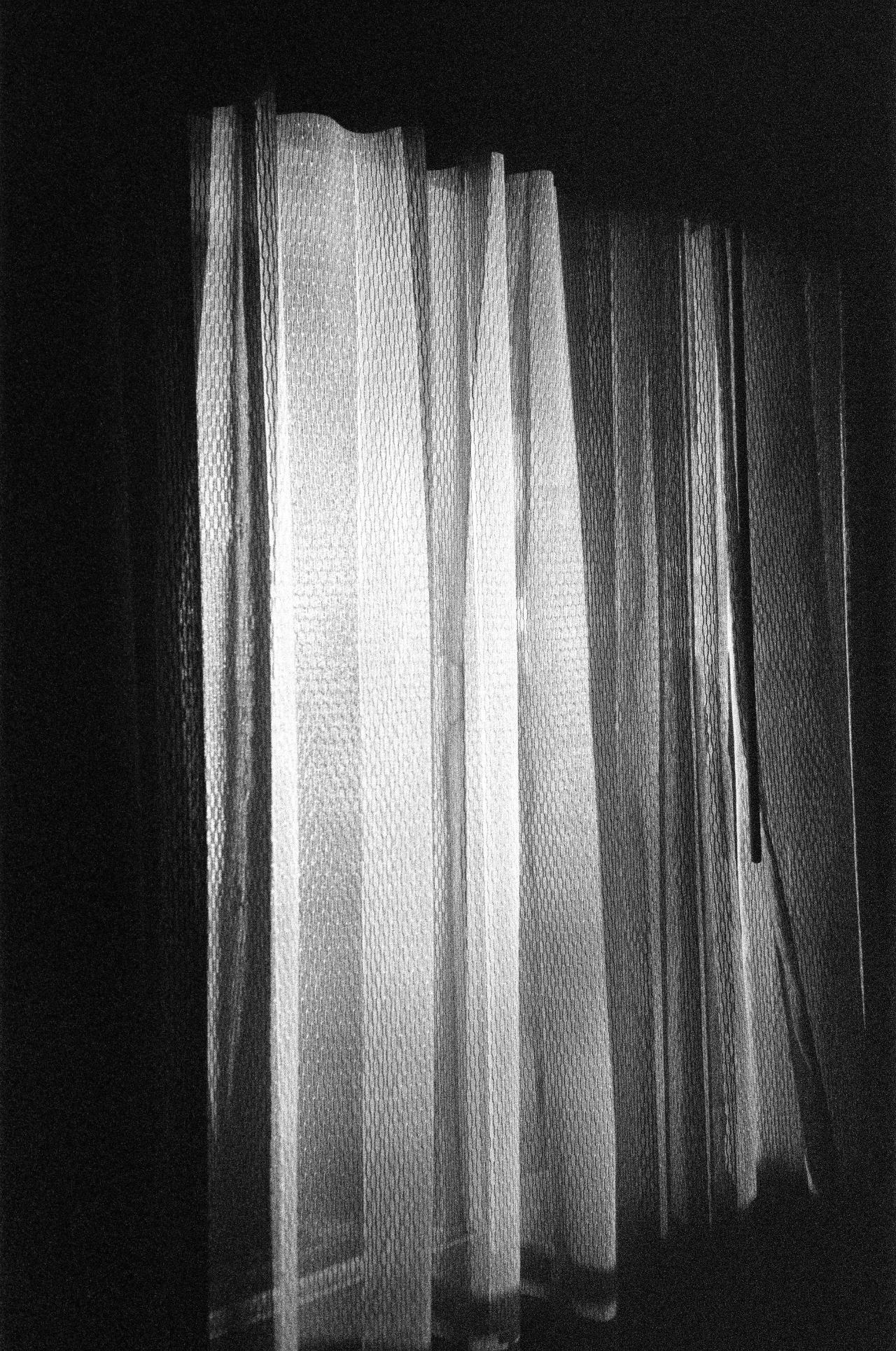

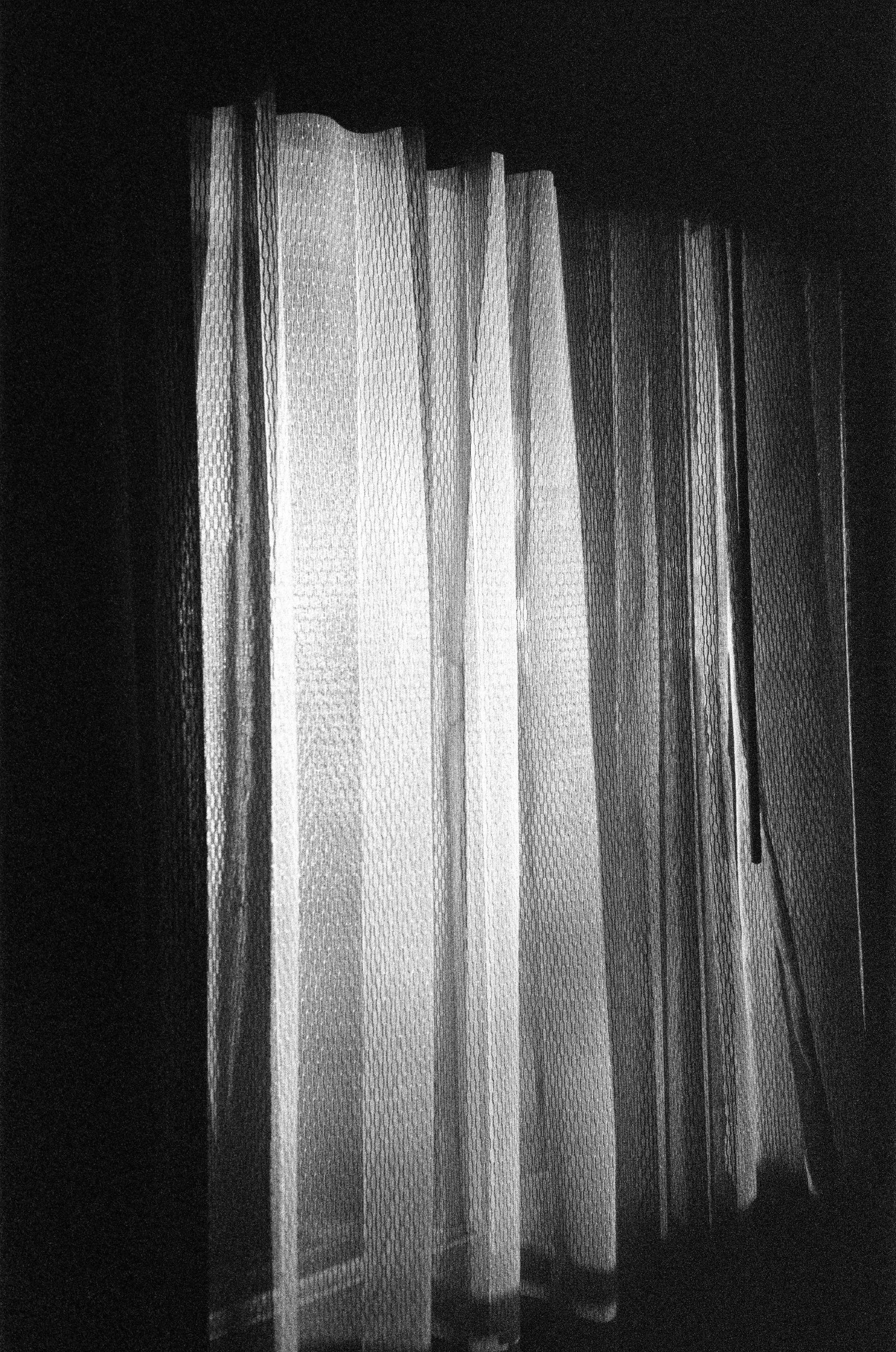

Window in California 2024. By Mads Kjeldgaard.

Hearing the chorus

The sheet music is in front of me. I stumble through the notes slowly, like an infant learning to read, spelling out each syllable patiently. One note after the other, each one a shocking revelation in itself. Is this music a piece of furniture? That would make it a dead, lifeless object in the room. To me it is something alive, a body swashing with blood, because I am playing it, and I am a human being, alive in this room.

The remnants of the last note ring out in the instrument’s iron frame. I find the next note with my fingers –harmonics decay to something barely perceptible – and press the keys with a motion as if tripping over a garden rake, my face finding the moist, grassy ground. As it fades out with the whole city in the background, I get a fuzzy feeling as I take it all in. There’s a poem by Whitman where he describes a similar experience:

Now I will do nothing but listen,

To accrue what I hear into this song, to let sounds contribute toward it.

…

It shakes mad-sweet pangs through my belly and breast.

I hear the chorus, it is a grand opera,

Ah this indeed is music—this suits me.

Neighbourhood magpies up to no good

The practice of chi gong commends the ideal of the crane: standing still by a lake, always ready to snap a fish in its beak. It’s not asleep, it’s not moving, it’s actively relaxed and fully aware of its surroundings. By the piano, in between notes, I become a crane myself, perceiving the sounds of my surroundings. I feel the wind rustling in my feathers, and I observe the creases in the water surface from the thick, slow raindrops, smeared out by the rolling caresses of the air that just passed me by.

Windows in California and Arizona 2024 by Mads Kjeldgaard.

Eventually, this slow approach becomes a new artistic practice for me. I place microphones on the iron frame of the piano to come closer to the strings as they are struck by the hammers, this allows me to hear the reverberation, the shimmering klang of the material at hand. I record it all using loopers running at different speeds and long durations, to be able to relisten to what I heard before but from the perspective of another point in time.

Every day, after my morning routines, I guide myself to the piano as if I was a waiter showing a guest to their seat. Once properly placed, I turn my attention to the sounds that leak from the open window in between the notes – I notice the banality of it, and I love it: bird feet rustling in the rain gutter above the window, it’s the neighborhood’s magpies scheming again. Tap-tap-tap. Tap-tap. Tap.

– Mads Kjeldgaard, Nørrebro, København, 2024

About Mads Kjeldgaard

Mads Kjeldgaard is a sound artist and composer from Denmark. His work explores presence and time – at the moment with a particular emphasis on slow music, silence and environmental sounds. He is the founder of the record label Exformal Records and is a member of The Danish Composers’ Society. Kjeldgaard studied Electronic Music Composition at the Danish Institute of Electronic Music (DIEM) at the Royal Academy of Music and has a degree in journalism from the Danish School of Media and Journalism.

Explore more releases

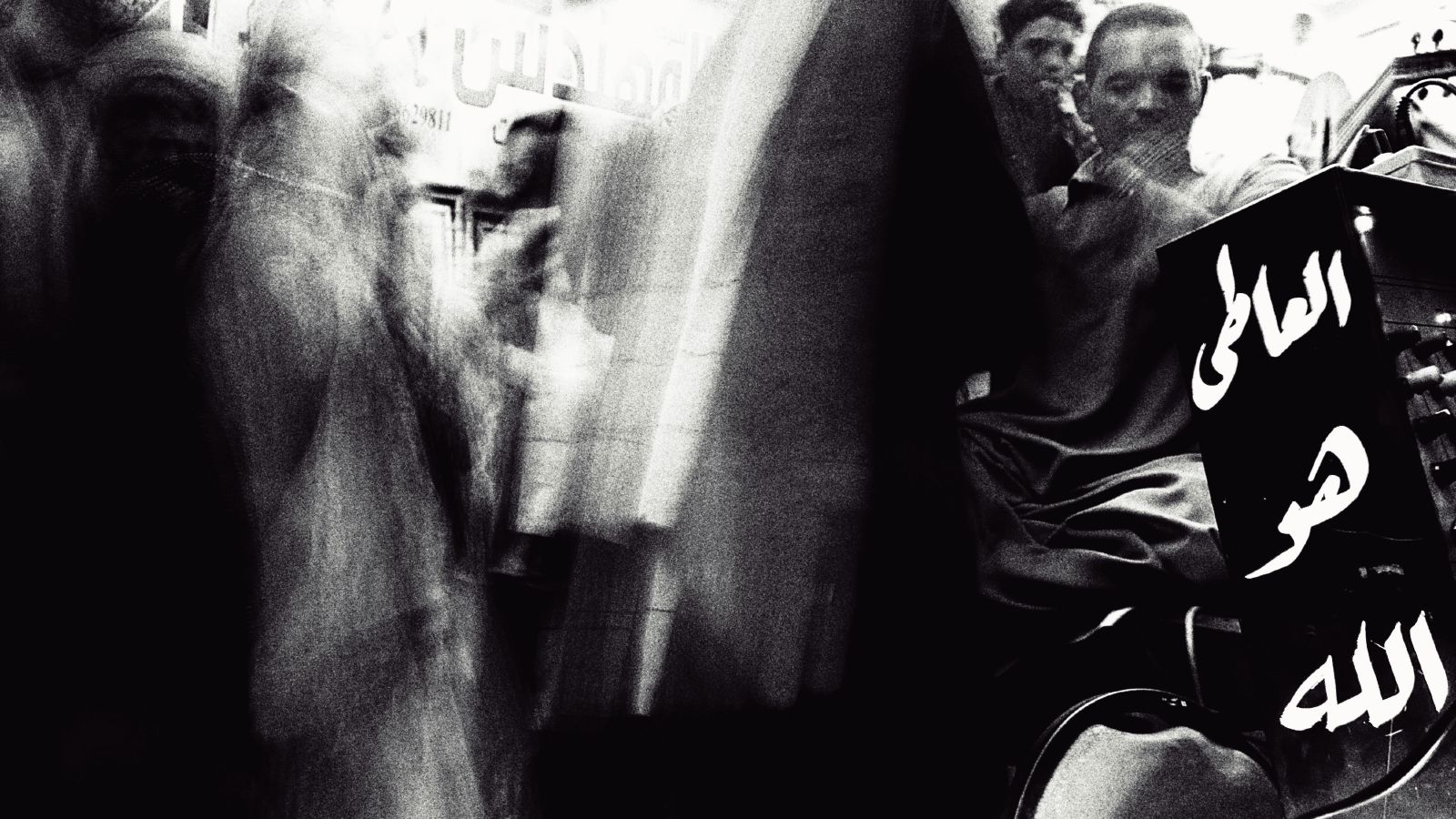

A dizzying, sonic tour of Egyptian devotional practices recorded over 5 years.

A problem occurred with the audio player. Here is some debug info:

Title: Valentina Ciniglio - morning dhikr shaykh Ayman - Sayida Nafisa 2023

MP3: /sound/03 Valentina Ciniglio - morning dhikr shaykh Ayman - Sayida Nafisa 2023.mp3

ID: 1760199459934175000

CSS ID: jquery_jplayer_1760199459934175000

Container ID: jp_container_1760199459934175000

Slow waves crash against the shoreline of the Atlantic island of La Gomera.

A problem occurred with the audio player. Here is some debug info:

Title: LFSaw - Taguluche Waves

MP3: /sound/lfsaw.mp3

ID: 1760199459934249000

CSS ID: jquery_jplayer_1760199459934249000

Container ID: jp_container_1760199459934249000

An audio essay about the so-called quiet zone in the Copenhagen S-train system.

A problem occurred with the audio player. Here is some debug info:

Title: Life in the Quiet Zone (narrated)

MP3: /sound/01 Mads Kjeldgaard - Life in the Quiet Zone (narrated).mp3

ID: 1760199459934327000

CSS ID: jquery_jplayer_1760199459934327000

Container ID: jp_container_1760199459934327000

Sound fishing in the third landscape between the rural and the urban. A collection of field recordings made while searching for something else.

A problem occurred with the audio player. Here is some debug info:

Title: Momento Celeste

MP3: /sound/09 Giuseppe Pisano - 09_Momento Celeste.wav.mp3

ID: 1760199459934394000

CSS ID: jquery_jplayer_1760199459934394000

Container ID: jp_container_1760199459934394000

The sonic experience of a thin strip of land dividing two seas.

A problem occurred with the audio player. Here is some debug info:

Title: Bella Comsom - As Far as the Sea Can Reach

MP3: /sound/Bella Comsom - As far as the sea can reach_web.mp3

ID: 1760199459934461000

CSS ID: jquery_jplayer_1760199459934461000

Container ID: jp_container_1760199459934461000

12 hours, 15 minutes and 7 seconds of minimalist background music. And a bag of tea.

A problem occurred with the audio player. Here is some debug info:

Title: Mads Kjeldgaard – Empty Cloud Part 8

MP3: /sound/emptycloudpart8.mp3

ID: 1760199459934542000

CSS ID: jquery_jplayer_1760199459934542000

Container ID: jp_container_1760199459934542000

Trancy drums and prepared piano improvisations from two of Copenhagen's finest instrumentalists.

A problem occurred with the audio player. Here is some debug info:

Title: Johanna Borchert & Anders Vestergaard - Excerpt

MP3: /sound/03 Johanna Borchert & Anders Vestergaard - Excerpt.mp3

ID: 1760199459934652000

CSS ID: jquery_jplayer_1760199459934652000

Container ID: jp_container_1760199459934652000

Slow ambient piano looping with the window open and the outside world seeping in.

A problem occurred with the audio player. Here is some debug info:

Title: Mads Kjeldgaard – 15:15 PM (Excerpt)

MP3: /sound/04 - Mads Kjeldgaard - 15_15 PM (Excerpt) (EX001).mp3

ID: 1760199459934719000

CSS ID: jquery_jplayer_1760199459934719000

Container ID: jp_container_1760199459934719000